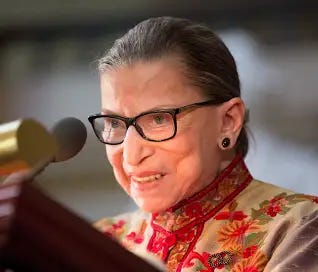

#16: Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the best advice she ever got

In 1993, Ruth Bader Ginsburg became just the second female Supreme Court justice in the court’s 200 year history.1

Given the exclusivity of this club—there have only been 116 Justices to date— anyone sworn in is probably worth studying. But RBG in particular, given what she went through to get there.

In the late 50s, when she was admitted to Harvard Law, RBG was just one of nine women in a school of 500 men. And even though she was at the top of her class, the dean—an outright sexist—would not let her finish.2 Undeterred, RBG transferred for her third year to Columbia Law, where she graduated top of that class.3 And this was all while she cared for her sick husband (also a law student, he’d be diagnosed with testicular cancer—more on him in second) and cared for their three-year-old girl.

After law school, Justice Ginsburg became a law professor at Rutgers, and started practicing on the side, winning some of the most important civil rights cases of the 1970s. In 1980, she was nominated to the US Court of Appeals in DC where she served for 13 years until President Clinton nominated her for the Supreme Court.

In her autobiographical, My Own Words, RBG takes us through this story, and the lessons she learned. Lessons of persistence, intelligence, the power of the written word—enough for 10 OGTs.

But none of those are what this OGT is about.

Because one of the most powerful pieces of advice RBG gives, is not about labor, but love. Not about IQ, but EQ. What RBG called “some of the best advice I ever got.”

And it came, oddly, from her mother-in-law.

When RBG met Marty Ginsburg, she was just a freshman government major at Cornell University. He stood out to her immediately.

“He was the only boy I ever met that cared I had a brain.”

Within a span of a few years, the two graduated from Cornell, got married, had a child, and were both admitted to Harvard Law School. Marty a great lawyer in his own right became a nationally recognized tax attorney and professor at Georgetown.

Their marriage seems to be the ideal we’re all searching for. At her swearing in to the Supreme Court, RBG said of her husband:

I have had the great good fortune to share life with a partner truly extraordinary for his generation, a man who believed at age 18 when we met, and who believes today, that a woman’s work, whether at home or on the job, is as important as a man’s.

What was the secret to their loving, sustaining marriage?

Obviously, there are a lot of factors. But RBG gives disproportional credit to a piece of advice she was given by Marty’s mother, Evelyn, on her wedding day.

‘In every good marriage,’ she counseled, ‘it helps sometimes to be a little deaf.’

I have followed that advice assiduously, and not only at home through fifty-six years of a marital partnership nonpareil. I have employed it as well in every workplace, including the Supreme Court of the United States. When a thoughtless or unkind word is spoken, best tune out. Reacting in anger or annoyance will not advance one’s ability to persuade.

The OGT

It “helps to be a little deaf,” is about a profound a phrase as I’ve ever heard.

It’s an elegant way of saying that you can choose the things to which you attribute importance, so choose wisely. People make errors, they get heated, they say things they probably regret—so let it go, it doesn’t matter, it won’t serve you. And not only people but events—you’ll get unlucky, or something other than what you deserved. Don’t pay attention, don’t listen, be a little deaf.

It’s like the great advice F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote to his daughter—about things not worth worrying about.

I think opposite is just as true: sometimes, it pays to listen to with great intent. To amplify those things which may make a small sound, but are disproportionately important.

And we’ll end with one of those important things—a letter that Marty, dying of cancer, wrote to RBG.

A letter she didn’t find until after he’d passed.

I found this letter in the drawer of the stand next to Marty’s bed in the hospital, when we knew it was the end, and I was taking him home so that he could die at home rather than in the hospital. I was just checking to see that we had everything he brought with him. And on a yellow pad there was a letter to me.

And it reads:

“My dearest Ruth, you are the only person I have loved in my life — setting aside a bit, parents and kids and their kids — and I have admired and loved you almost since the day we first met at Cornell some 56 years ago.” He was wrong about 56. It was nearly 60 years. We were married for 56 years. “What a treat it has been to watch you progress to the very top of the legal world. I will be in Johns Hopkins Medical Center until Friday, June 25, I believe, and between then and now, I shall think hard on my remaining health and life and consider, on balance, the time has come for me to tough it out or to take leave of life, because the loss of quality now simply overwhelms. I hope you will support where I come out, but I understand you may not. I will not love you any less.”

And just signed “Marty.”

Is there something that happened recently that you should have been more “deaf” to? Or something that you were deaf to that should have been given more attention?

I’ve got a list going.

Sebastian Maniscalco on long-term thinking

Mark Cuban on the one skill open to everyone that no one uses

Michelle Obama on how to change your career

Jeff Bezos on the difference between gifts and choices

Kevin Hart on how to bounce back after rejection

Arnold Schwarzenegger on how to find and copy a model

Tim Ferriss on the counterintuitive ease of thinking big

Rafa Nadal on how to beat someone more skilled than you

Oprah on the question to ask yourself before big decisions

Steve Martin on why persistence matters more than talent

Matthew Perry on helping others in your situation

Elizabeth Gilbert on passion versus curiosity

Phil Knight on what running taught him about business and life

Stan Lee on the secret to original thinking

F. Scott Fitzgerald on what really matters

The first had been Sandra Day O’Connor in 1981

According to RBG, in her first year, the dean had her and the other eight women for dinner and asked them, like a schmuck, “why are you at Harvard taking the place of a man?”

She also graduated top of her undergrad class at Cornell