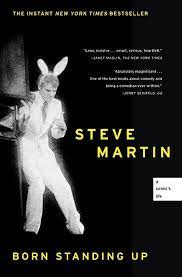

One Good Think #10: Steve Martin

Martin turning himself from awkward magician to successful standup

“Perseverance is a great substitute for talent.”

-Steve Martin-

The most pivotal moment in Steve Martin’s comedy career happened in 1973.

By that point, Martin, age 28, had already been in comedy for a decade, first as a just a performer (a sort of standup-magic hybrid) and then also as a writer for various comedic shows like The Smothers Brothers.

Along the way, Martin found some success. He wrote on well-known shows and managed to book plenty of gigs as an opener or “feature act” (not the headliner, but one step below), and even earn spots on TV, appearing on shows like The Steve Allen Show, The Mike Douglas Show, and eventually, The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson.

But the appearances weren’t good enough to spark a standup career. Despite legend, Martin learned, you had to appear on Carson many, many times before you developed any sort of brand name. And your name needs to sell tickets to be a headliner.

One day, after being turned down for an spot on The Dean Martin Show, Martin had a realization:

I understood I would never be hired in that situation, that the odds of confluence on a certain day of the producers’ desires, my talent, and a good reading were low, and that the audition process was a dead end. I decided to leave Hollywood and go on the road.

Martin made an agreement with himself: he would give it two years on his own. But if nothing clicked by the age of 30, he was done.

The story he tells it in his book, Born Standing Up (which I wrote about here). What he learned about persistence is the subject of today’s OGT.

Perseverance Over Talent

At age eighteen, I had absolutely no gifts. I could not sing or dance, and the only acting I did was really just shouting. Thankfully, perseverance is a great substitute for talent.

Despite a lack of natural ability, I did have the one element necessary to all early creativity: naïveté, that fabulous quality that keeps you from knowing just how unsuited you are for what you are about to do.

Martin had leveraged that persistent naiveté for nearly a decade. Now, on the road without a stable income or place to stay, he would test just how resilient he could be.

Martin was able to book shows across the country, but he often paycheck to paycheck, given the cost of travel almost equaled his pay.

I was getting jobs, but the travel costs were killing me. If I got five hundred dollars for an appearance, it would cost me three hundred just to get to it.

This went on for two years.

One thing the road did offer, however, was a chance to experiment. A chance to develop originality, and generally, as comics say, “build his act.”

In this netherworld, I was free to experiment. These out-of-the-way and varied places provided a tough comedy education. There were no mentors to tell me what to do; there were no guidebooks for doing stand-up. Everything was learned in practice, and the lonely road, with no critical eyes watching, was the place to dig up my boldest, or dumbest, ideas and put them onstage.

This led to improvement. But he was getting better without any tangible (read: monetary) results. That’s when he hit an inflection point.

Right around his 30th birthday, Martin was about to give in. He was just not seeing how things would change. He couldn’t keep going check to check. Tired from the road, he was close to heading home.

But then, after a seemingly normal Florida show, Martin got the most unexpected and important review of his life.

John Huddy, the respected entertainment critic for The Miami Herald, devoted his entire column to my act. Without qualification, he raved in paragraph after paragraph, starting with HE PARADES HIS HILARITY RIGHT OUT INTO THE STREET, and concluded with: “Steve Martin is the brightest, cleverest, wackiest new comedian around.”

The review gave Martin the positive feedback he needed, at the time he needed it most. And it also sparked a buzz around him, one that didn’t stop for the rest of the 1970s.

My review from John Huddy was the knock on the window just as I was about to get in my car and drive… it gave me a psychological boost that allowed me to nix my arbitrarily chosen thirty-year-old deadline to reenter the conventional world. The next night and the rest of the week the club was full, all ninety seats.

After that sellout week, things fell in place.

Martin started getting headline gigs around the country, and selling those out, eventually leading to the new phase of his life.

I was about to enter a phase of my life when three things would occur: I would earn money; I would grow to be famous; and I would be the funniest I ever was.

I did stand-up comedy for 18 years. Ten of those years were spent learning, four years were spent refining, and four years were spent in wild success.

I was seeking comic originality, and fame fell on me as a byproduct. The course was more plodding than heroic.

The OGT

“Perseverance is a great substitute for talent.” That quote stuck in my head.

Martin left Hollywood for the road against the advice of many. He had good writing jobs. He was appearing on shows. He was getting by. It seemed like he was “doing it.”

But what’s clear is that he knew what he wanted for himself: he wanted to be a performer, and a good one. He cared about quality and authenticity. And he was willing to endure to get to it.

But at the same time, it was nice to see that, just like the rest of us, Martin had doubts, too. Consistently. And he was able to push through, with the help of some good feedback and some good friends.

Do I have that sort of persistence in me?

Do you?

Go think on that.

Such a great story here. Nicely recapped.

The big question this leaves with me is about time. I usually think of perseverance as something we need over a decade or more. His "2 years by age 30" threshold was totally arbitrary, and this story really only has legs because he got that incredible review right as he was about to quit.

So take the other path—what if that review did happen, and his tour ended without the breakthrough, which is more commonly the case for most people building something new. Do we extend the timeline by another two years? Give up and build something new? I worry about survivorship bias in this one.