Jim Carrey on visualizing the future (#77)

How Carrey went from struggling actor-comedian to star

I’m a Jim Carrey diehard.

But even I didn’t know about a long, fledging time of transition a decade into Carrey’s career.

Carrey started standup in Toronto at the age of 15 (in 1977), and had some quiet, early success as a young, local impressionist. But after moving to Hollywood at 19 (1981), and getting some good early reception in the US—including performing at The Comedy Store, and appearing on The Late Show with Johnny Carson at the end of 1983—Carrey didn’t like where things were going.1

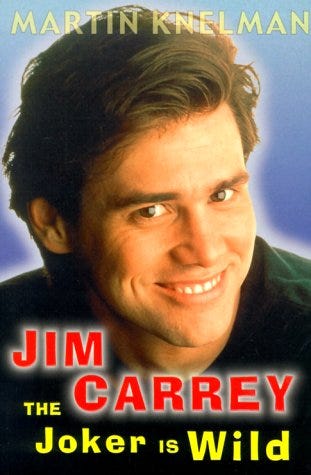

His act was largely based on absurd stunts and impressions, and one not necessarily respected by the “real” comedians. At the age of 23 (1985), on a particularly depressing tour with impressionist Richard Little in Las Vegas, Carrey finally lost it. As his biographer Martin Knelman tells it in, The Joker’s Wild: The Trials and Triumphs of Jim Carrey:

Las Vegas had come to symbolize the career path from which he was trying to escape. Carrey added in a later interview, "I realized I didn't want to be the guy doing the Cary Grant impression; I wanted to be Cary Grant."2

After this point, and for the next few years, Carrey went to a dark place. The key problem, Knelman writes, was a loss of self-belief.

According to Buddy Mora, his manager at the time, Jim was suffering from a severe loss of confidence in himself. This was partly because he was giving up his impressions, which had always brought him laughter and applause… “The old act gave Jim a leg up," Mora said. "When.. he stopped doing the old act, he lost that advantage...

That was around 1986.

Four years later, Carrey got booked on a sketch show created by Keenan Ivory Wayans called In Living Color. Four years after that, he was paid $350,000 to play a starring role about a pet detective named Ace.

None of us can hope for that sort of stardom. But it’s what he did to keep himself going—to hold himself up, to keep the dream alive—during his years of struggle that we can all learn from.

And that’s the subject of today’s OGT.

Talk To Your Future Self

During that transition period, in fall of 1987—right around the time his daughter Jane was born— Carrey started a routine to keep his dream alive.

He had a ritual of driving up to Mulholland Drive, where he could look down on all of Los Angeles. The journey represented his ascent to the peaks of Hollywood stardom.

He elborated on what he did up there on a Barbara Walters interview in 1995:

I would go “I’m a popular actor. Every director wants to work with me.” It was a way of dealing with being completely out of work… I would stay up there until I actually believed these things. Then I would drive down the mountain feeling like the biggest star in Hollywood.

Then, he did something special— a symbol of his commitment and his resolve. He wrote himself a check, eight years into the future.

Remembering the conversations about goal-setting he'd had years ago… Jim wrote a check to himself, dated several years in the future. The amount payable to Jim Carrey "for acting services rendered" was $10 million. It was a bet he was having with himself about the future. He hung onto the check for several years, determine that one day he would be able to cash it.

Jim later confirmed that the check was post-dated Thanksgiving 1995.

Eight years later, after Ace, Dumb and Dumber (for which he was paid $7,000,000), and The Mask in 1994, Carrey was offered a deal for The Mask 2 in 1995.

The amount: $10,000,000.

The OGT: Talk to your future self

It’s true that this has an air of—well, good for him, he’s so talented, blah blah. And maybe this all seems a little ‘manifesty’ to you.

I see it differently.

First of all, I see a guy who committed to a pursuit when he was 15 years old. Like Seth Rogen, Dave Chapelle, or Jerry Seinfeld, he made a commitment to comedy early, with laser focus. It’s not shocking for a guy with some talent and ambition, with that sort of early focus, to get really good 7-10 years later. Remember this: when he got In Living Color, he’d been doing comedy for nearly 15 years.

Second, how many “young talents” never make it out of that transition period Carrey had. They have great rookie seasons, only to fade under the pressure of celebrity, or the weight of uncertainty. Steve Martin, who had a remarkably similar story, was weeks away from quitting.

Third, though this might sound manifesty, the process of vividly imagining your future, goals, and even making a commitment to your future self, is a studied area of social science. “Episodic Future Thinking,” or Mental Time Travel as it’s more colloquially called, has research behind it. I would listen to Jane McGonigal’s take on this, if you’re interested.

Anyone familiar with Arnold’s writing or speeches, knows he did this all the time. He visualized himself as a bodybuilding champion who makes it to Hollywood. He went through it all of the time (here’s a quick clip of him talking about it).

The bottom line—if you’re pursuing a dream, you have to find a way to keep yourself afloat. Maniscalco committed to infinity. Cheryl Strayed told herself she was the toughest woman in the world. SPANX founder Sarah Blakely listened to Wayne Dyer.

Arnold and Jim Carrey visualized their dream.

What do you do?

He also landed a starring role on an NBC pilot called The Duck Factory, but it was cancelled in months.

A lot of the inspiration for not going the Vegas / Impressionist route was due to 1980s comedy legend, Sam Kinison. As Carrey would later say, "Sam made me sit back and say, 'here's a guy who is really doing something different and challenging the audience.'"