The Wright Brothers' genius trick to solve flight (#61)

How Orville and Wilbur figured out the precise shape of their plane to crack the code of lift

In 1899, virtually everyone felt human flight was impossible.

Everyone, that is, but a few extremist tinkerers, and two brothers in Dayton, Ohio named Wilbur and Orville Wright.

The Wrights—who were bicycle mechanics by trade—were inspired by bird theorists and hang-gliding enthusiasts who believed flight was possible. If 30 pound bustards1 could physically fly, the theory went, then a machine of similar dimensions should be able to as well. As David McCullough writes, in his book The Wright Brothers:

The works of Lilienthal and Mouillard, the brothers would attest, had “infected us with their own unquenchable enthusiasm and transformed idle curiosity into the active zeal of workers.”

As workers, there were three major problems the Wrights had to solve:

Keeping the plane in the air (i.e. lift versus drag),

Keeping it moving forward (i.e. propulsion) and

Controlling direction (i.e. turning in the air)

It was #1, lift—which comes from “air moving faster over the arched top of a wing, thereby making the pressure there less than that under the wing”— where their solution struck me as not only creative, but as applicable to creating anything: a plane, a business, or a film.

And that’s the subject of today’s OGT.

Lift is all about the proportion of wind going over and under the wings.

Precision is critical. To construct their first gliding machine, the Wrights used the dimensions from the most notable gliding experimenter that published them—one that completed 5,000 glides.

But, when the Wrights put those dimensions to the test, it didn’t work.

It was not just that their machine had performed so poorly, or that so much still remained to be solved, but that so many of the long-established, supposedly reliable calculations and tables prepared by the likes of Lilienthal, Langley, and Chanute—data the brothers had taken as gospel—had proven to be wrong and could no longer be trusted. Clearly those esteemed authorities had been guessing, “groping in the dark.” The accepted tables were, in a word, “worthless.” According to what Orville was to write years later, Wilbur was at such a low point he declared that “not in a thousand years would man ever fly.”

The Wrights had to create their own calculations from scratch.

Being mechanics, not mathematicians, their method was one of guess-and-check. But to guess-and-check various measurements, reconstruct a 20 foot plane using basic tools, cloth, and wood, and then test it multiple times, often crashing, would have probably taken years.2

The Wrights came up with a trick that shrunk that experimentation to months: the built a model.

For three months, working in one of the upstairs rooms at the bicycle shop, they concentrated nearly all of their time on these “investigations” and with stunning results. They devised and built a small-scale wind tunnel—a wooden box 6 feet long and 16 inches square, with one end open and a fan mounted at the other end, and this powered, since the shop had no electricity, by an extremely noisy gasoline engine. The box stood on four legs about waist high… For testing apparatus inside the box, they used old hacksaw blades cut to different sizes with tin shears and hammered into a variety of shapes and thicknesses—some flat, some concave and convex, or square or oblong, and each about six inches square and one-thirty-second of an inch thick—these strung on bicycle spoke wires.

Though such apparatus did not look like much, it was to prove of immense value. For nearly two months the brothers tested some thirty-eight wing surfaces, setting the “balances” or “airfoils”—the different-shaped hacksaw blades—at angles from 0 to 45 degrees in winds up to 27 miles per hour. It was a slow, tedious process, but as Orville wrote, “those metal models told us how to build.”

The disaster that almost made Wilbur quit was in the summer in 1901.

They started their wind-tunnel tests in late autumn, and with the resulting measurements, started to rebuild the gilder in the spring of 1902. It wasn’t until September 1902, a full year after their mishap, that the Wright brothers finally were about to test out the wind tunnel experiments.

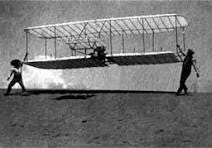

In ten days of practice they made more glides than in all the preceding weeks, and increased their record for distance to more than 600 feet. Altogether in two months on the Outer Banks they had made nearly a thousand glides and resolved the last major control problem.

…

They broke camp at first light on October 28 in a cold, driving rain and walked the four miles to Kitty Hawk to start the journey home and in a frame of mind far different from what it had been at their departure the year before.

All the time and effort given to the wind tunnel tests, the work designing and building their third machine, and the latest modifications made at Kill Devil Hills had proven entirely successful. They knew exactly the importance of what they had accomplished. They knew they had solved the problem of flight and more. They had acquired the knowledge and the skill to fly. They could soar, they could float, they could dive and rise, circle and glide and land, all with assurance.

Now they had only to build a motor.

The OGT: experiment with models

When Bruce Springsteen first was signed to Columbia Records, he had a lot of competition.

But there was one thing he had over them: many, tiny experiments. He didn’t run them in a wind tunnel, but in his bedroom, in his high school, and in dive bars along the Jersey Shore.

I was signed to Columbia, along with Elliott Murphy, John Prine and Loudon Wainwright, “new Dylan”s all, to compete in acoustic battle at the top of the charts with our contemporaries. What I had over my company in the field was that I’d secretly built up years of rock ’n’ roll experience out of view of the known world and in front of every conceivable audience. I’d already seen the roughest the road had to offer and was ready for more. These long-honed talents would go a ways in distinguishing me from the pack and helping me get my songs heard.

Henry Ford was first a machinist. He first experimented with steam-powered farm equipment, but feeling the impact was limited, and steam was not efficient enough, he moved to the combustion engine. Over the next decade+, he started small, then bigger, and built his first gas-powered car in 1896. Seven years later, he had the process down enough to start The Ford Motor Company.

“There was no guessing as to whether or not it would be a successful model,” Ford said, speaking of the Model T. “It had to be. There was no way it could escape being so, for it had not been made in a day.”

One key to the Wrights’ success was many, small experiments.

First, the wind tunnel. Then they flew the glider like a kite. Then they took short, safe glides of tens of feet, close to the ground. Then higher and further. Then they added a motor, a rudder, and the ability to warp the wings. This all happened over a decade, and it’s the same with anything hard, innovative, and long.

The message I take from the Wrights, and basically the message of anyone who knows about art, science, or entrepreneurship: If you’re building something great, find a way to experiment in small, iterative parts. Test it in your barn like Ford, or your high school stage like Springsteen.

First, like the Wrights, experiment in your wind tunnel.

Then try to fly.

A heavy bird.

Just constructing one glider took 3-4 months.